Context of the Trial at the Brazilian Supreme Court (STF)

The Brazilian Supreme Court (STF) is about to decide on Extraordinary Appeal No. 592,616 (Topic 118), scheduled for August 28, 2024. This appeal discusses the inclusion of the Service Tax (ISS) in the calculation basis of contributions to the Social Integration Program (PIS) and the Social Security Financing (COFINS). The highly anticipated decision could significantly impact public finances and service-providing companies.

Minister Luiz Fux, president of the STF, initially highlighted the topic but later canceled the emphasis, allowing the trial to proceed in the physical plenary. However, since the emphasis was canceled, the votes of retired justices who supported the thesis will remain valid, as will be further explained.

Divergence Among the Justices

In 2021, the virtual trial of Topic 118 resulted in a 4×4 tie, revealing the divergence among the justices. On one side, former Justices Celso de Mello, Rosa Weber, and Ricardo Lewandowski, who are now retired, and Justice Cármen Lúcia, who is still active, voted for the exclusion of ISS from the PIS and COFINS calculation basis, arguing that ISS is a temporary financial inflow and cannot be considered revenue.

On the other side, Justices Dias Toffoli, Alexandre de Moraes, Edson Fachin, and Luís Roberto Barroso defended the inclusion of ISS, arguing that the ISS tax collection technique differs from that of the non-cumulative ICMS.

It’s important to note that in the trial of Topic 69, Minister Luiz Fux supported that thesis, while Minister Gilmar Mendes opposed it. If the justices follow the reasoning previously adopted, whether in Topic 118 or Topic 69, it is likely that the tie-breaking vote will be cast by Minister André Mendonça.

Nature of ISS and ICMS

Both ISS and ICMS are taxes that do not permanently integrate into the taxpayer’s assets. They are transferred to the competent political entity and do not constitute the company’s own wealth. ISS, like ICMS, is an amount that passes through the company’s cash flow and is transferred to the tax authorities. Therefore, it cannot be considered as part of the company’s gross revenue or turnover.

Comparative Example

To illustrate the impact of excluding ISS, let’s consider an example of a consulting company with gross service revenue of R$ 10,000.00 and an ISS of R$ 400.00 (hypothetical rate of 4%).

With the inclusion of ISS in the PIS and COFINS calculation basis, the contributions’ basis is R$ 10,000.00, resulting in a PIS of R$ 165.00 (1.65%) and COFINS of R$ 760.00 (7.6%), totaling R$ 925.00.

If ISS is excluded, the PIS and COFINS calculation basis is reduced to R$ 9,600.00, resulting in a PIS of R$ 158.40 (1.65%) and COFINS of R$ 729.60 (7.6%), totaling R$ 888.00. The difference is R$ 37.00 less in taxes paid, representing a significant reduction in the tax burden.

The justices who defend the inclusion of ISS in the PIS and COFINS calculation basis argue that the ISS tax collection technique differs from that of the ICMS, which is non-cumulative. However, this distinction does not seem appropriate for the following reasons:

- ICMS Non-Cumulativity: The non-cumulativity of ICMS implies that the tax paid at one stage of the production chain can be offset at the next stage. However, this does not alter the fact that ICMS, like ISS, is an amount that passes through the company’s cash flow and is transferred to the tax authorities, as evidenced in the example above. In other words, the ICMS non-cumulativity technique does not justify the inclusion of ISS in the PIS and COFINS calculation basis, as both taxes do not permanently integrate into the taxpayer’s assets.

- Absence of Distinction in Accounting Operation: Both ISS and ICMS are transitional amounts that do not represent the company’s own wealth. Therefore, they should not be considered as part of gross revenue or turnover. The distinction between ISS and ICMS, raised by the justices for inclusion in the PIS and COFINS calculation basis, is unjustified, as both taxes have the same transitional nature and do not integrate into the company’s assets.

Still aiming to illustrate the controversy, consider the following data for application in a hypothetical operation (without considering any exclusion of ICMS from the contributions’ basis, as defined in Topic 69):

Goods Acquired for R$ 1,000.00

The taxpayer will need to separate the tax amounts to determine the real value of the product, i.e., its net value, as well as reserve the highlighted taxes to benefit from the credit at the end of the period. This is represented by the following accounting operation:

- D – Stocks (Asset) – R$ 727.50

- D – ICMS to recover (Asset) – R$ 180.00

- D – PIS to recover (Asset) – R$ 16.50

- D – COFINS to recover (Asset) – R$ 76.00

- C – Cash/Banks (Asset) – (R$ 1,000.00)

In the Sale Operation

Assuming the taxpayer resells the exact units previously purchased but for the amount of R$ 1,500.00, the following operation occurs in the case of ICMS:

- D – Cash/Banks (Asset) – R$ 1,500.00

- C – Sales Revenue (Result) – (R$ 1,500.00)

- D – ICMS on sales (Result) – R$ 270.00

- C – ICMS Payable (Liability) – (R$ 270.00)

- D – PIS on sales (Result) – R$ 24.75

- C – PIS Payable (Liability) – (R$ 24.75)

- D – COFINS on sales (Result) – R$ 114.00

- C – COFINS Payable (Liability) – (R$ 114.00)

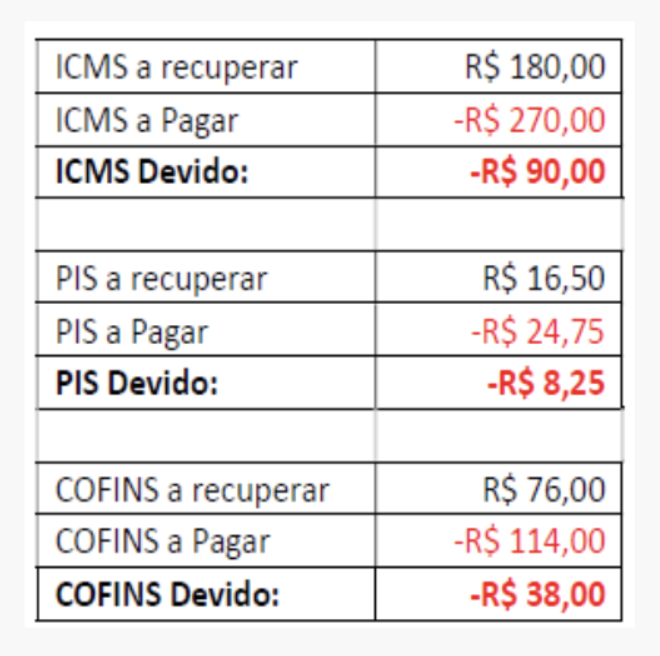

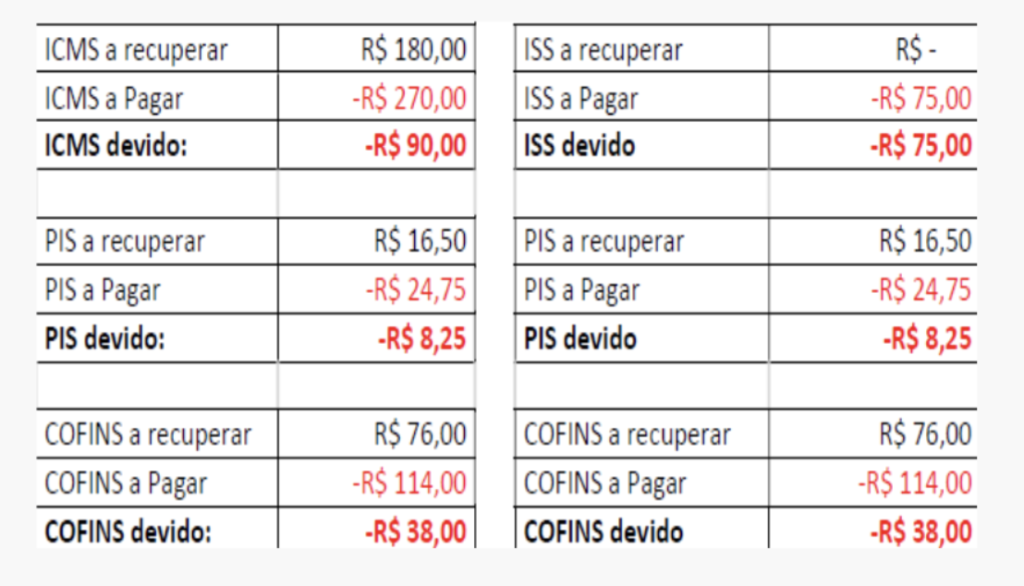

This operation will be repeated for all product sales made by the commercial company, with the highlighted amounts being those the company will have to pay:

In the Case of a Service-Providing Company (ISS)

For a similar operation, replacing the data pertaining to a commercial company (as reported above) with a service-providing company (subject to ISS), we have the following:

Goods Acquisition

- D – Inputs (Result) – R$ 907.50

- D – PIS to recover (Asset) – R$ 16.50

- D – COFINS to recover (Asset) – R$ 76.00

- C – Cash/Banks (Asset) – (R$ 1,000.00)

Service Provision Operation

Based on the example above, when analyzing the operation as a service provision, the following registration method applies:

- D – Cash/Banks (Asset) – R$ 1,500.00

- C – Service Revenue (Result) – (R$ 1,500.00)

- D – ISS on sales (Result) – R$ 75.00

- C – ISS Payable (Liability) – (R$ 75.00)

- D – PIS on sales (Result) – R$ 24.75

- C – PIS Payable (Liability) – (R$ 24.75)

- D – COFINS on sales (Result) – R$ 114.00

- C – COFINS Payable (Liability) – (R$ 114.00)

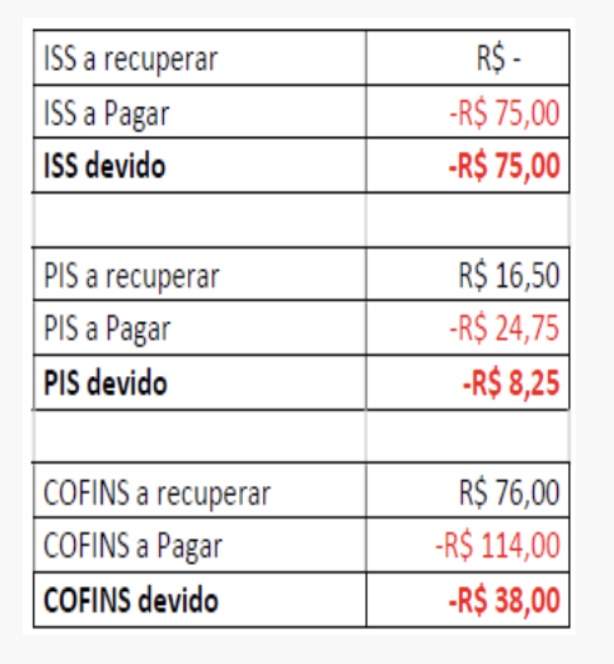

At the end of the period, the comparison between tax credits and debits will be made, following the model of apportionment transcribed below:

Comparison Between a Commercial Company (ICMS) and a Service-Providing Company (ISS)

It can be observed that there is no change in PIS/COFINS concerning ISS in relation to ICMS. The fact that ISS is a cumulative tax does not impact the final tax amount in the current calculation method of contributions. It is entirely irrelevant to the core issue, which concerns the improper and unconstitutional inclusion of the tax in the contributions’ calculation basis, as it clearly includes tax revenue transferred to the competent political entity as part of the gross revenue/turnover.

Conclusion

The analysis of the arguments and the comparative example demonstrates that excluding ISS from the calculation basis of these contributions aligns with fundamental principles of tax justice and economic common sense, honoring the ephemeral nature of taxes and their non-constitution as part of the business assets, i.e., the concept of “gross revenue.”

The attempt to distinguish between ISS and ICMS, aiming to justify its inclusion in the PIS and COFINS calculation basis, lacks foundation in the operational and accounting reality of companies. Both taxes, by their nature, do not fixate in the taxpayer’s assets, acting merely as transitional values destined for transfer to the tax authorities. This fundamental characteristic intrinsically excludes them from being considered part of the revenue or gross income for tax purposes by PIS and COFINS.

This topic emerges as a necessary intervention to address yet another legal distortion and promote a more transparent and effective tax system. Therefore, it is expected that the STF’s decision, upon concluding the judgment of Topic 118, will align with the understanding previously established in the judgment of Topic 69, solidifying the comprehension already adopted by the Court regarding the concept of “gross revenue,” thus establishing legitimate bases for the incidence of these contributions.

A decision different from that adopted in Topic 69, in addition to compromising jurisprudential coherence and the functionality of what is termed legal certainty, will only legitimize the lack of confidence of taxpayers in the judiciary, who, unfortunately, fear another politically convenient decision at the expense of any logical legal reasoning in favor of companies, the true sustainers of wealth circulation and the economy in the country.

By Janini Denipoti and J. Marcello Gurgel